this post was submitted on 11 Oct 2024

197 points (99.0% liked)

196

16410 readers

1905 users here now

Be sure to follow the rule before you head out.

Rule: You must post before you leave.

founded 1 year ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

This is how a lot of maths is already done by computers. For example, it's basically impossible to get a computer to do an integral of an arbitrary function, but there are a lot of methods to approximate the answers. And that's mostly by using "slide rule" methods of approximately getting the right answer. The computer just does it fast with smaller intervals than you'd do manually.

I’m aware of how computers use numerical methods to get numbers that are good enough for a given precision.

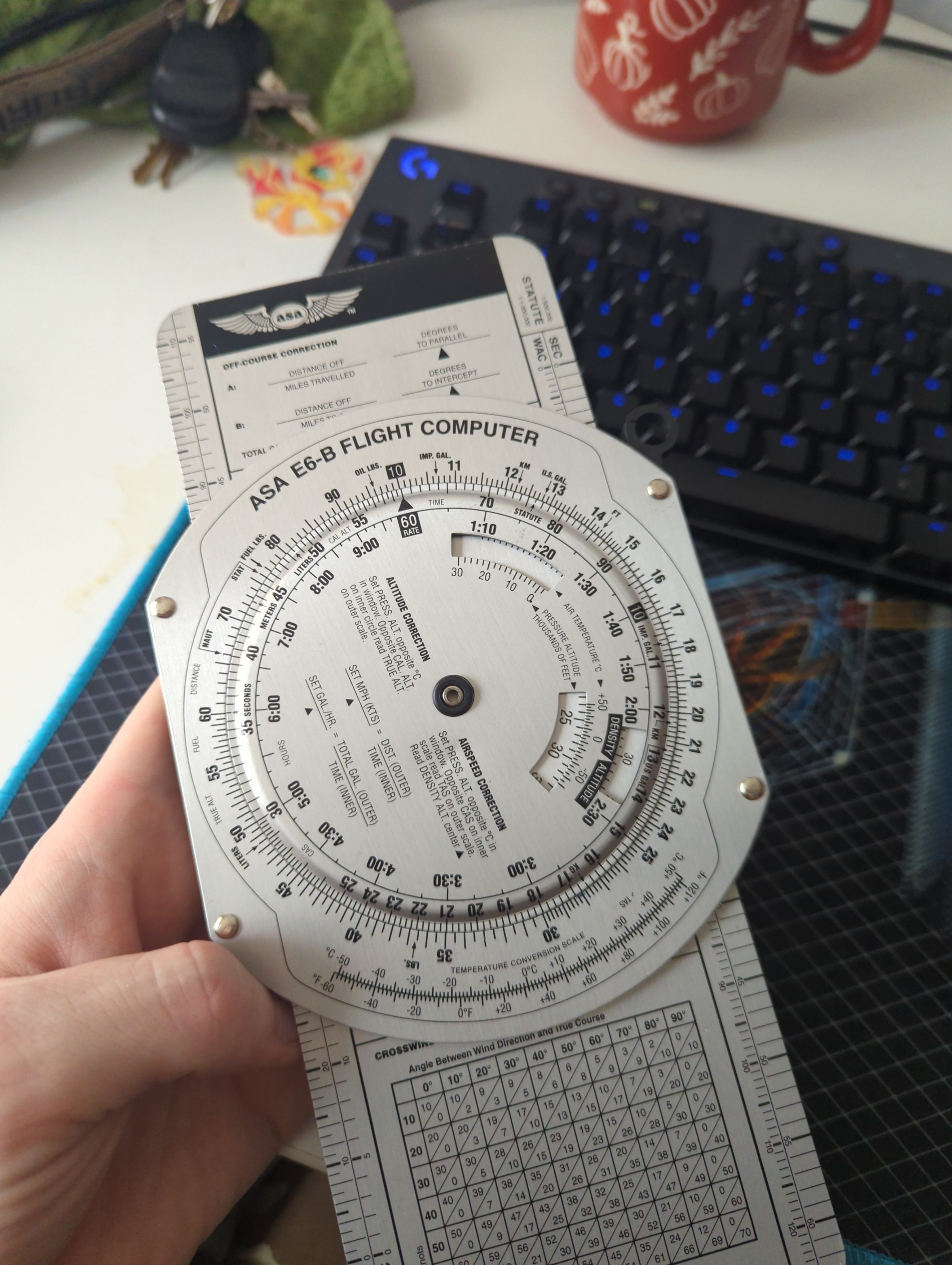

I meant more like a robust way to create physical slide rules for arbitrary uses. Here’s a set of tables of baking ratios, I want to comfortably look up x for a known y. That kind of thing.

I think what you really want is nomogram, which is like a non-moving sliderule in the form of a graph, which is great for "If I have X of thing A, and Y of thing B, how much of thing C do I get/need?" questions like baking ratios.

Unforuntately, I can't really find an nomogram generators online that I can get to work (though that might be a me-problem, and not a website problem)

There's a bit of a difference though between those computer driven iterative digital numerical methods and an analog continuous geometric object. It's like comparing pixel density and film grain. At a fine enough precision they become difficult to distinguish, but they are not the same. You could definitely use iterative methods to build a "continuous" solver at an arbitrary precision. We pretty much have to do it that way for any signficantly complex function.

Sorry, this comment got away from me and feels kind of incoherent now. I'm just trying to say that analog and iterative digital methods have subtle differences that one should remain aware of.